Central Park Is & Has Always Been Hella Queer

Tracing the LGBTQ history of Manhattan's biggest park from 1857 to today

Since its creation in 1857, Central Park has had numerous affiliations with the LGBTQ community and its history, including its Angel of the Waters sculpture on the Bethesda Fountain designed by lesbian sculptor Emma Stebbins, its role in several early Gay Pride Marches, and its multiple areas used for gay cruising and socializing, particularly the region in the park known as The Ramble, which continues to this day to be a meeting place for predominantly gay and bisexual men.

Perhaps the first queer component to Central Park came as early as 1873 with the commission of Bethesda Fountain, the only sculpture sanctioned as a part of the Park’s early design. The Park Commission directed that the sculpture be dedicated to “Love,” an instruction that sculptor Emma Stebbins may have handled literally. It's speculated that she modeled Angel of the Waters after her lover, Charlotte Cushman, a leading American actress. The statue was also the earliest public artwork by a woman in NYC. More than a century later, the Bethesda Fountain and its Angel of the Waters statue would serve as a primary symbol and locale in Tony Kushner’s groundbreaking play, Angels In America, which with great complexity examined both AIDS and homosexuality in America during the 1980s.

Stebbins’ Angel of the Waters certainly isn’t the only quietly queer monument in Central Park. Others include the statue of Fitz-Greene Halleck along the Mall’s ‘Literary Walk’, who can be found posed with his legs crossed a little too tightly over one another and his hand dangling quite daintily out to the side. Who is Halleck you might ask? Well, he was a satirical poet of the mid-19th century and the private secretary to John Jacob Astor, and his statue here is the first ever in the U.S. erected to a poet. Its unveiling in May 1877 was even attended by President Rutherford B. Hayes and his entire cabinet. That being said, Halleck is also considered an early American gay icon, seeing as he never married and is strongly believed to have been a homosexual. At 19, Halleck was enamored with a young Cuban named Carlos Menie, to whom he dedicated a few of his early poems, and was later on rumored to be in love with his close friend, Joseph Rodman Drake.

Other queer statues scattered around Central Park include the monument to William Shakespeare, located at the southern end of the Mall in the “Literary Walk” as well the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, located Mid-Park at 68th, which features the likenesses of Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Shakespeare, Anthony, and Stanton have all long been speculated to have had same-sex relationships during their lifetimes.

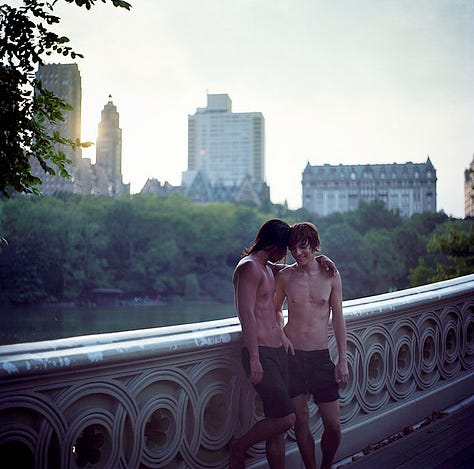

In his book Gay New York, author George Chauncey identified Central Park as a major LGBTQ social center and cruising ground and goes on to name multiple areas that were popular meetup points over the years, particularly for gay and bisexual men. At the turn of the 20th century, men would tend to meet next to Belvedere Castle, but by the 1910s the benches near Columbus Circle became the prominent pickup site. In the 1920s, the lawn at the north end of the Ramble became so popular that it earned the nickname “The Fruited Plain.”

In the ’30s, other spots heavily trafficked by gay men were the area just south of 72nd Street, the area near Columbus Circle, Bethesda Fountain, and the walkway from the southeastern corner of the park to the Mall, which became known as “Vaseline Alley” or “Bitches’ Walk”. Chauncey also noted that as early as 1921, police began being sent into the Park to entrap and arrest gay men. Among those arrested in the Park were diarist Donald Vining in 1943 and future gay rights leader Harvey Milk in 1947. To date, however, The Ramble still remains a highly popular spot for outdoor sex, despite the numerous arrests and gay bashings that have occurred there over the decades.

On Stonewall's 1st anniversary, a march set out from Greenwich Village toward Central Park, culminating in a "gay-in" at Sheep Meadow. The initial march became an annual event, (a.k.a what has become the Pride Parade) but for two decades the parade route involved Central Park. In 1973, the march actually began in Central Park and ended in Washington Square Park. In 1974, the march was moved back to Sixth Avenue, once again traveling uptown, where it ended at Central Park’s Sheep Meadow. By 1981, the march was going north up Fifth Avenue to 79th Street, ending on the Great Lawn. It was later moved again, beginning at Columbus Circle and following Fifth Avenue south to the Village.

At the time that it occurred, no one could foresee the legacy that the first Pride march in New York, then called the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, would have. In fact, the flier announcing the event stated, in part: “What it will all come to no one can tell. It is our hope that the day will come when homosexuals will be an integral part of society — being treated as human beings.” The flier added that such a change “can only be the result of a long hard struggle against bigotry, prejudice, persecution, exploitation — even genocide.” It further read, “Gay Liberation is for the homosexual who stands up, and fights back.”

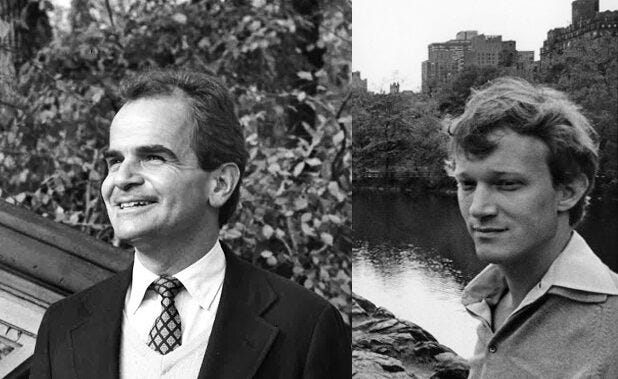

By the 1980s, Central Park was in desperate need of landscape restoration. Integral to the planning and implementation were two gay landscape architects, Philip N. Winslow and Bruce Kelly, who were also two of the authors of Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan (1985). Winslow designed the landscape restorations of Bethesda Terrace, Cherry Hill, the Mall, and the Point, while Kelly was also involved in the restoration of the Point, the Ramble, the Great Lawn, the Dene, and the Shakespeare Garden. Kelly also famously designed Strawberry Fields, a gift of Yoko Ono in memory of her husband John Lennon, which was dedicated in 1985.

Sadly, both Winslow and Kelly would later succumb to AIDS. Both men died in their 40s—Winslow in 1989 at age 48, and Kelly in 1993 at age 44. “It was Bruce who improved my own Olmstedian eye on our many walks in different sections of the park,” wrote Betsy Barlow Rogers, founder of the Central Park Conservancy, in her book Saving Central Park.

Around the same time, AIDS activism was at its peak, and Central Park served as a stage for several demonstrations. One of the most notable events occurred in 1989, when activists unfurled thousands of panels of the AIDS Memorial Quilt on Central Park’s Great Lawn, reading out the names of countless victims of the disease. It was part of a campaign that began in 1987 to raise awareness of the pandemic and fund AIDS research. After they were displayed on the Great Lawn, the quilt panels were then sent to San Francisco and combined with another quilt section there. To date, the AIDS Memorial Quilt is now the largest piece of folk art on Earth, with over 48,000 individual panels and counting.

The legacy of AIDS also continues to play a role in Central Park today. For over 30 consecutive years, AIDS Walk New York, the largest single-day AIDS fundraising event in the world, has taken place in Central Park each year in the month of May. The walk has inspired nearly 890,000 people to raise more than $150 million to combat HIV and AIDS thus far and will continue to do so with each new walk and new generation of participants.

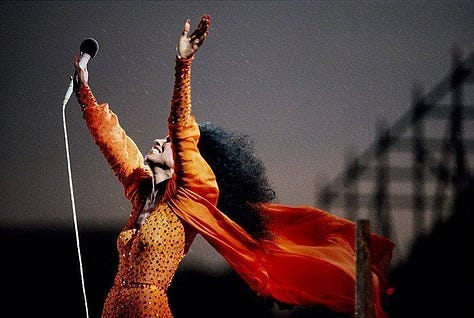

On a lighter note, perhaps one of THE gayest things to occur in Central Park took place on July 21, 1983 during a Diana Ross concert held on The Great Lawn. The concert was staged as a benefit to raise funds for a children's park, but was cut short by a massive lightning storm, with winds of nearly 50 mph being reported. Ross, a premiere gay icon and true professional, continued to perform as the rain and winds pelted her, her signature hair and billowy cape whipping all around her (the video is a must watch). It has become one of the most canonically iconic gay performances of all time: TV Land awarded it the Most Memorable Television Performance in 2006, ABC chose it as one of the Top 20 Television Performances ever and VH1 included it on its list of 100 Greatest Moments on TV of all time.

More recently, since same-sex marriage became legally recognized in New York as of July 24, 2011, Central Park has become a haven and mecca for gay proposals, wedding photoshoots, marriage ceremonies and more. Central Park’s website even has its own section highlighting this fact, stating: “Central Park welcomes all couples, including same-sex and gender neutral, to walk down the aisle in a quintessential New York City wedding ceremony!…We look forward to sharing the joy of your wedding ceremony and creating a history of same-sex weddings in Central Park!”

So since its very inception, Central Park’s history has been intertwined with many facets of LGBTQ history, and it continues to this day to serve, in all its pockets, paths, and hidden coves, as a beloved gathering spot for queers of all kinds.