From Hollywood To Chinatown: The Queer Pioneer Who Was Esther Eng

The world's first female Chinese-American filmmaker was an out lesbian who ran five successful restaurants in New York City.

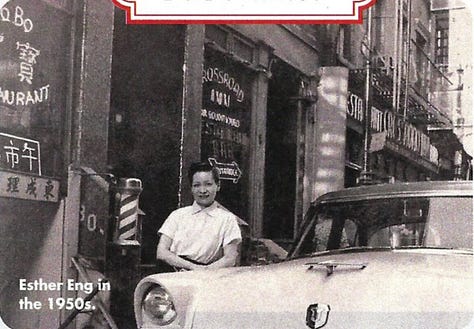

A true gender rebel, Esther Eng lived a life that was truly both fascinating and enigmatic—and also one of a kind. Born in the U.S. but fluent in Cantonese, she made a name for herself by becoming the world's first female Chinese-American filmmaker, all while rejecting social expectations by donning masculine attire and sporting a “mannish” haircut. Simultaneously, she felt little need to hide her frequent and often publicized romantic and sexual relationships with other women, many of whom would also have starring roles in her films. Tragically, most of Eng’s cinematic creations have been lost to history, but the largely forgotten queer pioneer ultimately pivoted and lived a second life when she became an extremely successful restaurateur in New York City. Indeed, in her later years, Eng owned and operated five noteworthy restaurants in the City, and reportedly even had her ex-girlfriends manage the places. Esther Eng was thus not only a pioneer in the film industry, she is also often credited with influencing New York’s culinary landscape.

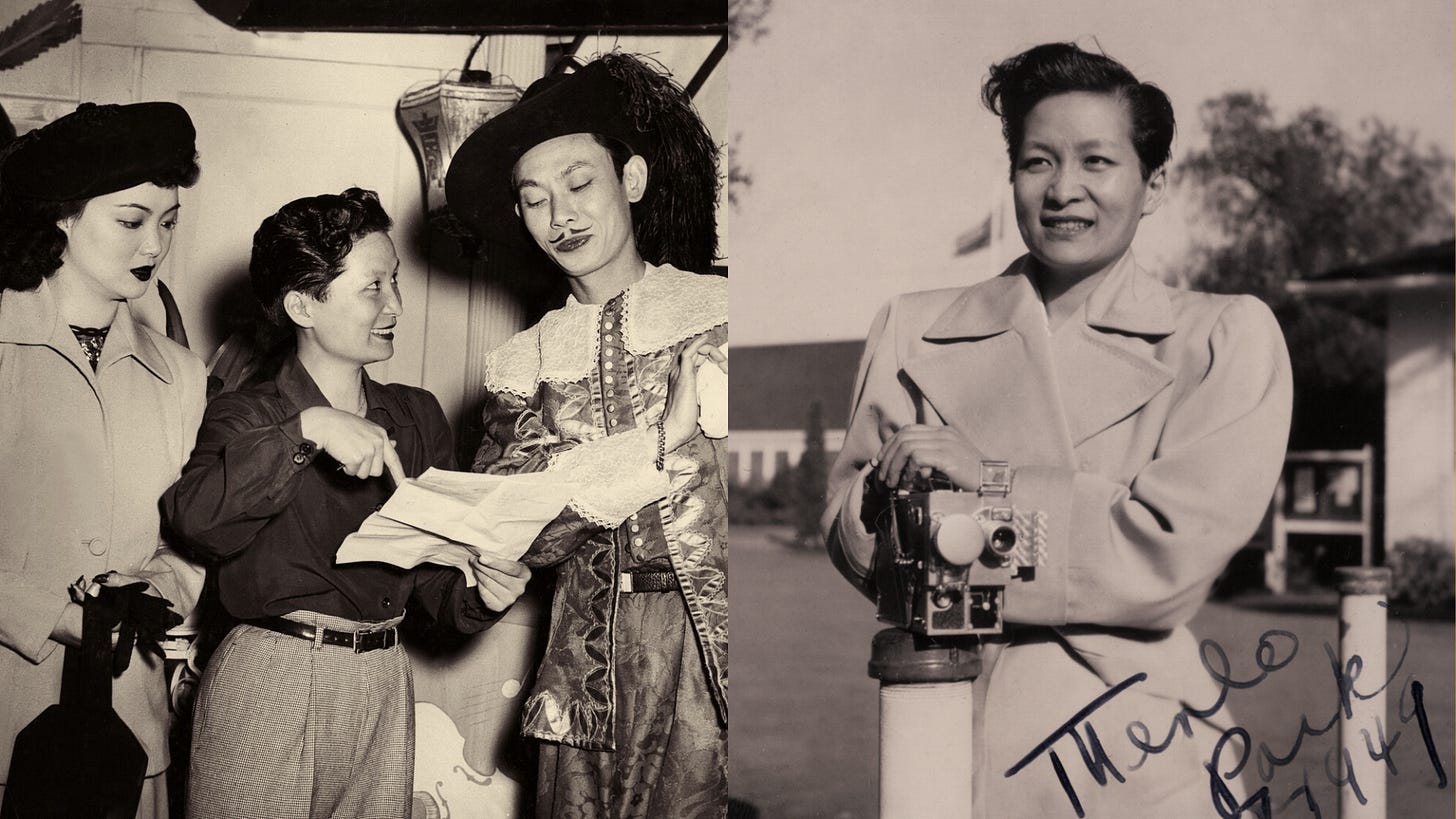

The fourth out of a whopping ten children, Esther Eng was born Ng Kam-ha on September 24th, 1914 in San Francisco, where she was raised in a home located at 1010 Washington Street. Her grandparents had come to America from Taishan county in southern China's Guangdong province. Growing up in SF, Eng developed a love for the theater and for movies in particular, and spent a lot of time at several of the city’s successful Chinese-language venues which frequently hosted some of China's most talented artists. This included, at the time, many Chinese actresses who were reveling in their newly acquired freedom, in the wake of a recently-lifted Chinese ban on female performers. Eng often fraternized with many of these famous Cantonese singers and actors who were performing at these theaters, and as soon as she was old enough to work, she took a job at the Mandarin Theater, one of SF’s preeminent venues located at 1021 Grant Avenue. Around this time, she developed a very close romantic relationship with the opera singer Wei Kim Fong, who would later become one of her cinematic muses. The two women were together from around 1934 to 1938.

When she was nineteen years old, Eng's father, Ng Yu-Jat, and a couple business partners decided to start a new business venture to promote Chinese culture and pride. Towards the end of 1935, they founded the Kwong Ngai Talking Pictures Company (a.k.a Cathay Pictures Ltd.) and proceeded to work on its first production, Heartaches (1936). Given her passion for the theater and close connections to many in the Chinese acting community, Esther’s father brought her into the company, and she became one of the film’s co-producers. Heartaches, a nine-reel Chinese-language romantic drama set in the context of contemporary Sino-Japanese conflicts, was made in just eight days at a studio on Sunset Boulevard and was billed as "the first Cantonese singing-talking picture made in Hollywood.” Its plot centered on a woman’s profound and patriotic sacrifice for the sake of her country, which aligned with the Chinese nationalist culture that was prevalent to this era. Eng's influence on the film, however, was in the decision to have a female be the story's ultimate hero (played by her girlfriend, Wei Kim Fong, no less), which added a fresh feminist perspective to an otherwise well-known narrative arc.

In 1937, when China entered into war with Japan, Eng then went to Hong Kong where she directed her first film, National Heroine (1937), about a female pilot fighting for her home country. The film continued Eng’s vision to feature a female protagonist, but unlike Heartaches, whose lead was a weepy victim of love and war, National Heroine portrayed a brave woman fighting alongside male comrades to defend China’s honor. The film was highly successful, was celebrated as an ode to Chinese womanhood, and Eng was subsequently awarded a "Certificate of Merit" from the Kwangtung Federation of Women's Rights as a result. These accolades and rising recognition encouraged Eng to stay in Hong Kong for the next three years. She proceeded to direct another two films: Ten Thousand Lovers and Storm of Envy, which were both released in 1938. She then co-directed the film A Night of Romance, A Lifetime of Regret with Wu Peng and Leung Wai-man and in 1939 made the film It's A Women's World (a.k.a 36 Amazons), which notably (and perhaps much to Eng’s pleasure) comprised of an all-female cast and showcased the daily lives and professional labors of thirty-six different Chinese women working in various professions.

A variety of reasons led to Esther Eng’s subsequent return to the United States in 1939, including her family's concern for her safety during the considerably volatile time. Additionally, two of Eng’s intimate relationships with women—one being with the actress Wei Kim Fong—had recently come to an abrupt end. At first, Eng returned to San Francisco, where she continued making movies until 1949. In 1941, she directed Golden Gate Girl, which notably saw the film debut of Bruce Lee, though he was an infant at the time (and in fact played a baby girl in the film). While reviews for this film were generally favorable, Eng was unable to leverage it into making further U.S.-based productions. When World War Two ended, she returned to Hong Kong with a plan to make another two new films, though these both unfortunately fell through.

By mid-1947, Eng returned yet again to California, where she was able to successfully make a film called The Lady from the Blue Lagoon/The Blue Jade, starring the Cantonese opera singer, Fe Fe Lee (Siu Fei Fei). Eng followed this up with another several films starring Lee, including Back Street (1948), Too Late For Springtime (1949), and Mad Fire, Mad Love (1949). During this time period, Eng and Lee were incredibly close and, much like Wei Kim Fong before her, Lee would later be identified as one of Esther Eng’s various girlfriends from over the years. The year 1949 would also see Eng’s involvement in the film industry begin to significantly wane—with the end of the Chinese Civil War that same year, many of the Cantonese opera and film actors that had supported Chinese language filmmaking in the U.S. decided to return to China and Hong Kong, significantly draining the talent pool.

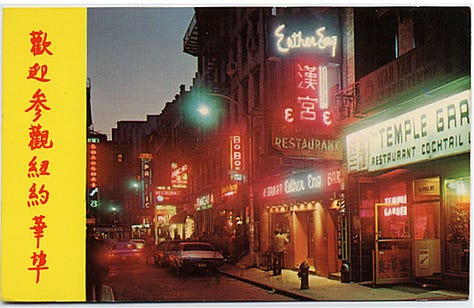

In 1950, Eng curiously moved to New York City, where she eventually took up residence in in Manhattan's Chinatown neighborhood, in an apartment complex located at 50 Bayard Street between Elizabeth Street and the Bowery. It is unclear what exactly drove Eng to the Big Apple, but her life and career would take a complete turn when she soon encountered an old acquaintance named Bo Bo, a Chinese actor who had been staying in New York with his troupe of non-English-speaking Chinese actors. Bo Bo and his crew had been reluctant to return to China due to its recent conversion to Communism. Eng then opted to manage his stage career in the United States, but also decided she would open a restaurant in order to provide these actors both with employment and the opportunity to learn English. Located at 20½ Pell Street in Chinatown, Eng opened her first restaurant in 1950, and decided to call it, of all things, Bo Bo.

Bo Bo quickly became both a haven for out-of-work Chinese actors but also was a massive success, serving customer favorite dishes like lobster egg rolls, bird nest soup, and duck with lychee. In 1964, The New York Times critic Craig Claiborne gave it a rave review, writing that “the only trouble with Bo Bo's is its extreme popularity…At times it is next to impossible to obtain a table [but] the fare is worth waiting for.” Although at this point Eng had seemingly shifted the focus of her career, she still remained deeply connected to her roots—Bo Bo’s matchbooks featured an image of a Cantonese opera singer as well as the tagline “the home of Chinese actors,” serving as a tribute to the restaurant’s theatrical origins and staff makeup. In 1959, Eng ultimately sold her stake in Bo Bo’s, but only as soon as she felt comfortable that the staff spoke enough English to be able to run the establishment themselves.

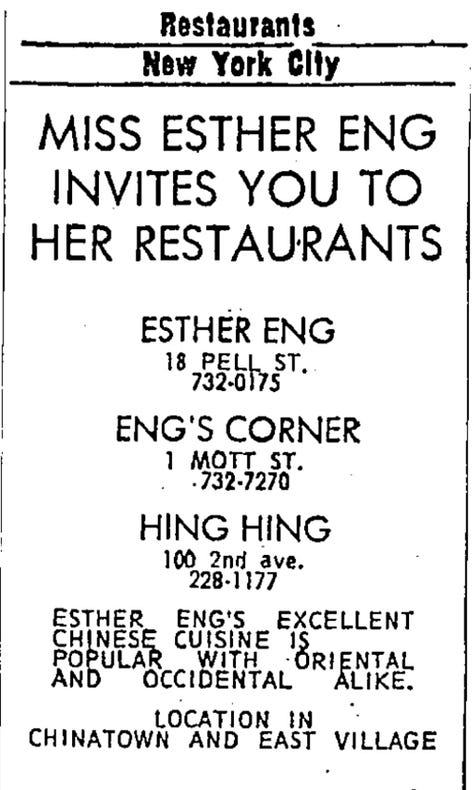

Buoyed by the massive success of Bo Bo’s, Eng then went on to build a mini culinary empire, opening four additional restaurants in New York City between 1950 and 1967. These were, respectively, Macao (located at 22 Pell Street), Hing Hing (100 Second Avenue), Eng's Corner (1 Mott Street), and the eponymously named Esther Eng (First opened at East 57th Street and Second Avenue, then relocated to 18 Pell Street). Each of Eng’s five restaurants achieved varying degrees of success, though the one named after herself, alongside Bo Bo’s were the most notable. Meanwhile, Eng’s Corner was a purportedly a popular drinking destination in particular for gay men. During this stretch, Eng additionally kept her ties to the cinema by running the Central Theatre in New York, where she exhibited films that she had acquired in Hong Kong and where she sometimes invited Cantonese opera singers to perform.

For much of her life, Esther Eng maintained a look composed of masculine dress and “mannish” haircuts. She was often referred to by the nickname Brother Ha, derived from her real name, Ng Kam-Ha. Press coverage throughout Eng's cinematic career often commented on her unique presentation, and also often highlighted her close relationships with other women, usually referring to them as Eng’s “bosom friends” or “good sisters.” During the 1930s, it is possible that what seemed to be a cultural acceptance in China of Eng's same-sex relationships and masculine presentation may, in part, have been due to the popularity at the time of all-female opera troupes with male-impersonating actresses. But somehow, despite the fact that this culture had dissipated in China in the ‘40s, not to mention the pervasive homophobic fever that suffused Cold War American culture in the 1950s, there seems to be no apparent record that Eng ever felt compelled to “correct” her gender presentation to one that was more conventionally "feminine” or to try and hide her same-sex romantic and sexual interests.

Esther Eng was even more unabashed about her sexuality later in life. In his 1998 memoir, Tea That Burns: A Family Memoir of Chinatown, Bruce Edward Hall recounted that “[All her restaurants] cater to the well-heeled two-martini crowd, but Esther Eng's is the first to eliminate 'combination' dinners and American food from her menus. Esther is also unusual because she is an outspoken lesbian, always seen wearing men's suits and 'mannish' haircuts. Her ex-girlfriends (of whom there are several) manage her other places uptown.”

On January 25th, 1970, Esther Eng tragically died from cancer at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. Despite all her accomplishments and the many lives she had already seemingly led, she was was somehow still only 55 years old. Eng was buried in Colma, CA where her grave remains to this day. Having never fully lost the itch, Eng did end up making one last movie in 1961 before she passed on, called Murder in New York Chinatown, which she co-directed with Wu Peng. Peng filmed all of the movie’s scenes set in Hong Kong, while Eng filmed the scenes set in New York. Sadly, this film, along with Golden Gate Girl (1941), are the only two Esther Eng films that are currently known to exist in a viewable format. The rest have seemingly been lost to history, waiting to be found. In fact, Eng herself was largely forgotten about as well until a 1995 column in Variety brought new attention to her and urged film historians to delve into her body of work.

Over forty years after her untimely death, a documentary film about the life and career of Esther Eng premiered at the Hong Kong International Film Festival in 2013. The film, entitled Golden Gate Girls (trailer above), was created and directed by the Chinese filmmaker, historian, film producer, writer and professor S. Louisa Wei. Wei was inspired to make the film in part after she had discovered several of Eng's photo albums in a San Francisco dumpster in 2006, which were collectively dated from 1928 to 1948. In an interview with the online publication SFGate, Wei told reporter Eddie Kim: “I can’t think of a better word to describe Esther than chutzpah. She was often the youngest and most inexperienced person on a set yet seemed to know how to work with all manner of people, without hesitation.”

During the film’s production, Wei did extensive research and was able to uncover several more of Esther’s photo albums, but not a single audio or video recording of Eng in existence. In the search process, though, Wei also discovered a strikingly nonchalant remark about Eng's gender presentation and sexual identity, made in a 1938 issue of the Chinese newspaper Sing Tao Daily News. Even back then, and in a conservative country like China, the reporter at the time publicly noted that Eng's "work, address, manner, and dress," along with her "sensibility that was completely that of a man," made her the "living proof of the possibility of same-sex love."