When NYC's Piers Were Queer

Serving many functions, the Christopher Street Pier has over the decades been one of the most vital spaces for New York's LGBTQ community

A meeting place, a hangout, a refuge. An industrial wasteland, a locale for sex, a beach, a dance floor, an art gallery, a home. A place of thrills, of danger, of comfort, of joy. Each of these varying descriptors and functions—alongside many others depending on who you ask—could at one point be attributed to a singular area in New York City: Greenwich Village’s waterfront, also known as the Christopher Street Pier.

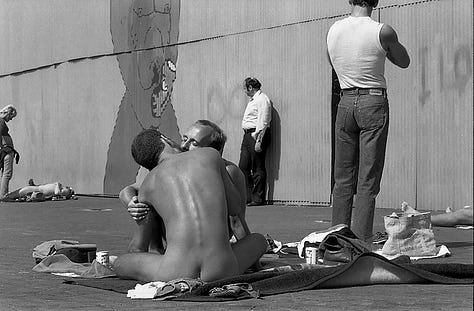

Once a working part of New York City's industrial waterfront, the Christopher Street Pier—a group of piers typically comprised of the piers along Manhattan’s West Side numbered 42, 45, 46 and 51, has long served as a vibrant social gathering site for the LGBTQ community, particularly used as a place for nude sunbathing, cruising and sexual intercourse. Now known as the Hudson River Park on the Hudson River waterfront of Manhattan's Greenwich Village, the Pier has over the decades also served as living quarters for queer homeless youth, a casual hangout and meeting spot for LGBTQ groups of friends, and a blank canvas for many notable queer artists to create site-specific installations.

By the early 20th Century, Greenwich Village's Hudson River waterfront and its numerous piers and shipping terminals served as New York City's busiest port for cargo and trans-Atlantic passengers. By WWI, however, the area had already become a popular cruising ground for gay men and by WWII the combination of unmarried, working class men, several seedy dive bars and the waterfront’s relative isolation made it a central hub for gay life in the City. By the early 1960s, industrial shipping and the workforce that came with it were largely moved out of the area and the piers were left largely abandoned. This allowed for a community of predominantly gay men, seeking isolation and refuge, to fully take over the piers and use them as a destination to meet one another for cruising and sex, particularly late at night when darkness and shadow allowed for cover.

By the 1970s, the nearby Christopher Street had become a Main Street of sorts for gay life in the City, and the dilapidated structures of the piers became a primary destination for LGBTQ folk by day as well, particularly to sunbathe nude, hang out, and engage in more publicly visible acts sex. Meanwhile, numerous gay bars and clubs began popping up in the vicinity to accommodate the crowding area, including the likes of Badlands, Sneakers, Keller's, Ramrod and Peter Rabbit's, among others. The Pier was just another stop on a newly forged gay circuit.

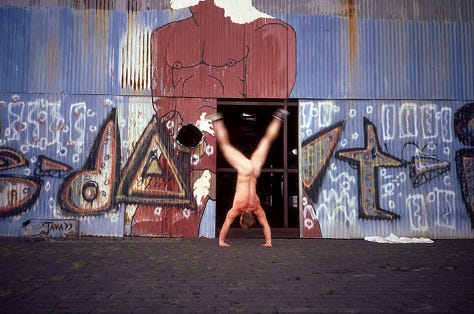

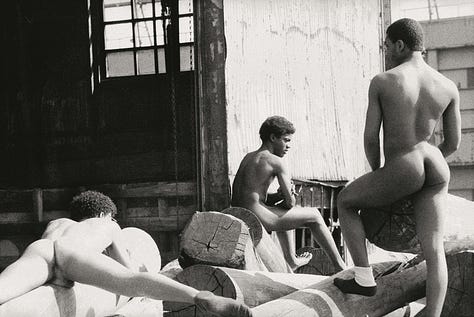

The piers and their dilapidated structures also became important spaces for numerous artists, such as photographers Alvin Baltrop, Stanley Stellar, Leonard Fink, Shelley Seccombe, Arthur Tress, Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz and Frank Hallam, who took countless photos of the piers’ decrepit structures and of their colorful inhabitants in various poses and states of undress. Many of these photographers’ work taken at the piers would go unrecognized and under-appreciated for decades, but now serve as incredible archives of gay City life in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

Additionally, between 1971 and 1983 the enormous interiors and abandoned offices of the piers’ ruin-like terminals were host to a diverse range of site-based installations and murals by multi-disciplinarian artists like Wojnarowicz and Hujar alongside Keith Haring, Luis Frangella and Gordon Matta-Clark, who famously created his work Day’s End by cutting out giant amorphous holes in the walls of the structure on Pier 52, which allowed unique beams of light to flow into the abandoned structure at sunrise and sunset. In 1983, Wojnarowicz, alongside fellow artist Mike Bidlo, even sent an open invitation out for an “artists’ invasion” of Pier 34. After several murals had been painted on the abandoned pier, Wojnarowicz declared: “This is the real MoMA.”

By the 1980s, the piers and the environment they fostered began to be affected by both the AIDS epidemic as well as by early waterfront improvement plans being put into effect by the City. At this time in particular, the piers became a haven as well as a home for many marginalized queer youth of color and trans folk. Two particular trans activists of color, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, established a strong presence in the area, doling out food and clothing to needy recipients who would be frequently found loitering in the area. Rivera herself made the piers her home in the mid-80s, and there are several devastating videos showing her struggling with being homeless there and ultimately being evicted from the area by the City.

In May 1995, Rivera at one point even tried to end her life by walking into the Hudson River. Marsha P. Johnson’s body, meanwhile was found floating in the Hudson River off the Piers in July 1992, and though police initially called it a suicide, friends of Johnson’s insisted that was not possible given it was not in Johnson’s nature and that several people had seen a group of men harassing Johnson shortly before her death. Still, the piers remained a vital refuge for queer youth of color, who often had nowhere else to go, and as the decade wore on, breaking, vogueing and other dance forms could be observed happening along the pier. Many scenes from the seminal 1990 documentary Paris is Burning by Jennie Livingston were shot in the area.

Planning to rebuild and revitalize the entire waterfront from the Battery to Chelsea began in the early ‘90s, a process which completely disregarded the presence and needs of the vibrant queer community there. This sparked a grassroots effort for LGBTQ participation and representation that endured for years, including 1998’s “Queer Pier” campaign which hoped to salvage the Christopher Street Pier as a vital space for the community. In the year 2000, FIERCE (Fabulous Independent Educated Radicals for Community Empowerment) was founded by a group of primarily LGBTQ youth of color, which hoped to bolster community organizing and ensure that the needs of queer youth would be addressed during the renovation of the Christopher Street Pier.

The piers officially closed in 2001 and were completely revamped throughout the early 2000s, slowly developing the area into the squeaky clean, gentrified Greenwich Village waterfront that stands there today. In 2018, New York State’s first memorial to the LGBTQ community was installed near the Christopher Street Pier, an abstract work by Anthony Goicolea that consists of nine boulders arranged in a circle to honor the victims of the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando (…why here?). Meanwhile, in 2014 the Whitney Museum commissioned artist David Hammons to develop a permanent public art piece along the pier. Hammons entitled the work Day’s End, directly referencing Matta-Clark’s work of the same name from 1975, and is an open structure that precisely follows the outlines, dimensions, and location of the original shed in which Matta-Clark created his version.

Given its proximity to both Greenwich and the West Village, The Christopher Street Pier today stills serve as a central gathering place for NYC's LGBTQ community, though these days it’s generally used for hanging out, meeting friends and sunbathing, albeit with clothing on. A visit to the Pier today can still feel cruise-y at the right times, but for the most part the nudity and public sex are no longer. It can still feel like a queer space, however, and that’s something that should never be washed away.

I’ll end with some of the numerous folks who commented their memories of and reminiscences from the Christopher Street Pier:

Andre Shoals (@frozinemn) commented: “Aww the days! And the nights! 😮”

Richard Pordon (@pordon_richard) added: “We did have a blast ❤️”

TJ (@deathandfood) reminisced: “I used to hang out there in the early ‘90s as a homeless queer kid. Ended up not going back to NYC for almost 15 years. Didn’t recognize the piers at all or I should say what they became. Glad to know queer folks still go.”

Finally, Paul Lewis (@paul.h.lewis.888) summed it up best: “The piers of the ‘70s were the great equalizer. You’d see prince and pauper, stunning and run-of-the-mill. It was a great big party that spilled over from Christopher Street.”

See below for more incredible shots from the piers over the years by, in order: Stanley Stellar, Shelley Seccombe, Andreas Sterzing, Stanley Stellar, Alvin Baltrop, Arthur Tress, Stanley Stellar, Valerie Shaff & Peter Hujar.

References & Further Reading:

Anderson, F. (2019). Cruising the dead river: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s ruined waterfront. The University of Chicago Press.

Bender, D. (2018, January 13). Walking christopher street: Pier 45. Charenton Macerations. https://www.charentonmacerations.com/2014/06/23/pride-2014-christopher-street-pier-45/

Berman, A. (2020, June 8). No money for Hudson River Park, but lots of money for Fantasy Pier Island - Village Preservation. Village Preservation - Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2014/11/17/no-money-for-hudson-river-park-but-lots-of-money-for-fantasy-pier-island/

Betsky, A. (1997). Queer Space: Architecture and same-sex desire. William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Chauncey, G. (2019). Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay male world, 1890-1940. Basic Books.

Codrea-Rado, A. (2024, July 28). A timeline of Christopher Street, New York LGBTQ Nightlife’s most storied thoroughfare. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/christopher-street-timeline-pride-2016-history/

Doherty, M., Galiher, S. A., Caramela, S., Phillippi, K., Davis, M. A., II, A. F., & Jenkins, D. (2024, August 9). Life for homeless gay and trans teens in New York City. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/meet-the-pier-kids-the-homeless-gay-teens-of-new-york-656/

Dowell, C. (2022, March 13). Looking back to when Paris was burning - village preservation. Village Preservation - Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2016/08/01/paris-is-burning-25-years-later/

Evans, H. (2022, May 2). Go west! – the leather & denim scene in the Weehawken Street Historic District - Village Preservation. Village Preservation - Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2022/05/02/go-west/

Green, A. (2015, June 24). We’re still queering the pier. amNewYork. https://www.amny.com/news/were-still-queering-the-pier/

Grillo, E. (2019, August 5). How Alvin Baltrop captured the Queer History of NYC’s West Side Piers. Interview Magazine. https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/alvin-baltrop-bronx-museum

Hanhardt, C. B., & Choe, Y. (2014). Safe space: Gay neighborhood history and the politics of violence. Duke University Press.

Journey To The Christopher St. Pier & Loss of Queer Spaces. Tenzmag.com. (2019, June 14). https://tenzmag.com/journey-christopher-st-pier-loss-queer-spaces/

Kaiser, C. (1999). The Gay Metropolis: 1940-1996. Phoenix.

Lustbader, K. (2017, March). Greenwich Village Waterfront. NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/greenwich-village-waterfront/

Moskowitz, P. (2023, May 26). Back on Christopher Street: Charting the change of West Village’s Gay Haven. Out Magazine. https://www.out.com/news-opinion/2017/4/03/back-christopher-street-charting-change-west-villages-gay-haven

Moskowitz, S. (2020, May 13). Walking the meatpacking district with GVSHP’s historic Image Archive - Village Preservation. Village Preservation - Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2018/07/30/walking-the-meatpacking-district-with-gvshps-historic-image-archive/

Muñoz, J. E., Chambers-Letson, J. T., Ochieng’ Nyongó, T. A., & Pellegrini, A. (2019). Cruising utopia: The then and there of Queer Futurity. New York University Press.

Pomeleo-Fowler, S. (2024a, July 3). The original “day’s end:” Gordon-Matta Clark’s ‘anarchitecture’ on Pier 52 - Village Preservation. Village Preservation - Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2024/07/03/the-original-days-end-gordon-matta-clarks-anarchitecture-on-pier-52/

Pomeleo-Fowler, S. (2024b, August 21). Looking back at the West Village Waterfront - Village Preservation. Village Preservation - Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2024/08/21/looking-back-at-the-west-village-waterfront/

Seliger, M. (2016, July 25). The Trans Community of christopher street. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/08/01/the-trans-community-of-christopher-street

Shepard, B., & Smithsimon, G. (2011). The beach beneath the streets: Contesting New York City’s public spaces. Excelsior Editions/State University of New York Press.

Swanson, C. (2015, November 18). Manhattan’s west side piers, back when they were naked and Gay. Intelligencer. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2015/11/west-side-piers-when-they-were-naked-and-gay.html

Walker, R. L. (2011). Toward a fierce nomadology: Contesting queer geographies on the Christopher Street Pier. PhaenEx, 6(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.22329/p.v6i1.3153

Weinberg, J. (2019). Pier groups: Art and sex along the new york waterfront. The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Winchell, L. (2020, June 15). Westbeth photographer Shelley Seccombe documents the Greenwich Village waterfront since 1970 - village preservation. Village Preservation - Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2020/06/02/westbeth-photographer-shelley-seccombe-documents-the-greenwich-village-waterfront-since-1970/

This is the NYC my gay 'uncles' tell me about. Great piece, thankyou. Times change, it's OK. Every generation shapes the places it needs.