Where To See Keith Haring For Free in NYC (Part 2)

A comprehensive guide to all the places in New York City where you can still ogle a work of art by the great Keith Haring at no cost (Part 2 of 2)

In a continuation from last week’s newsletter, here are several more places where you can still spot an original work of art by Keith Haring in New York City without having to crack open your wallet:

Woodhull Medical Center, 760 Broadway (Brooklyn)

The only work on this list situated in Brooklyn at 760 Broadway in Bedford-Stuyvesant, the joyously colorful mural that Keith Haring created for the otherwise unremarkable lobby of Woodhull Hospital can very much be seen for free, though you might want to feign illness in order to do so. The 700-foot long mural was painted by Haring alone in 1986, and the artist in fact offered to render it at his own expense, perhaps as a thank you to the hospital for its early dedication to healthcare access during the HIV/AIDS crisis. Haring at one point explained his inspiration for the piece, remarking that when he visited the hospital, he noticed a border running around the lobby that was “an intricate part of the architecture” which he wanted to “embellish…with a frieze of characters.”

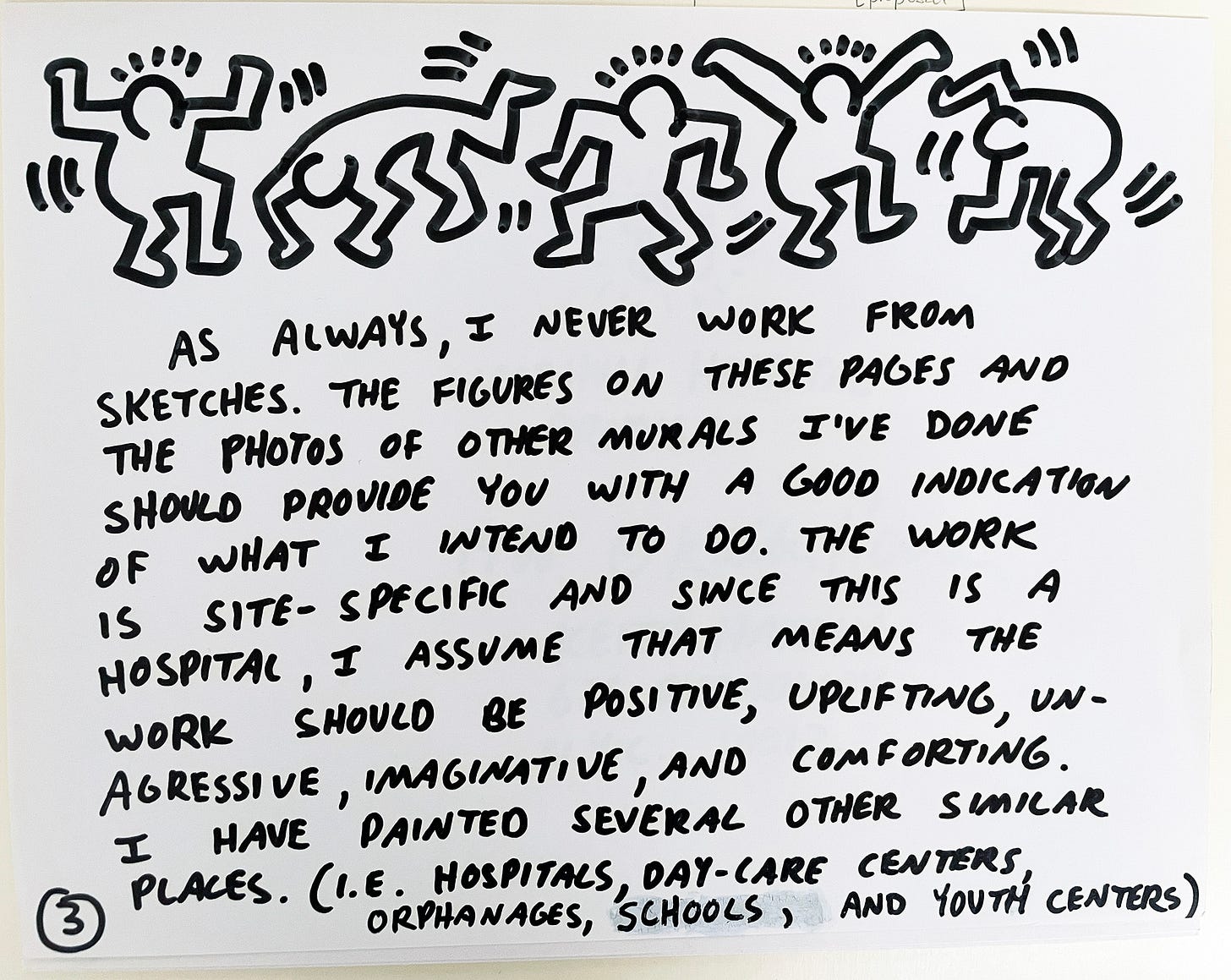

“My sense is that he just wanted to be of service,” said Gil Vazquez, executive director of the Keith Haring Foundation, in The New York Times, “Art heals, and he knew that.” At the time. Haring submitted a formal application to the City in order to be able to create the mural, in which he wrote: “Since this is a hospital, I assume that means the work should be positive, uplifting, unaggressive, imaginative and comforting.” The completed mural, which consists of a brightly colored parade of playful characters who appear to be wiggling and writhing in mirthful dance, certainly fulfills Haring’s intended mission.

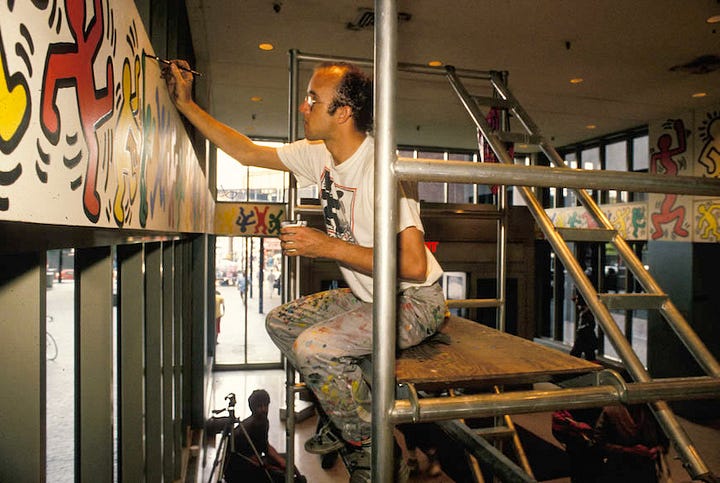

The entire Woodhull mural took Haring a full week to paint, and due to its height, the artist primarily painted it while sitting or standing on movable scaffolding. During breaks from painting, Haring came down from the structure and joined hospital staff, patients, visitors and fans to sign autographs, and created designs on poster boards and t-shirts for anyone who asked. Haring’s mural at Woodhull additionally extends out from the lobby down two separate corridors. The hallway mural figures, however, are simply painted in black-and-white, but have more details than the lobby mural’s figures, including faces and clothing.

Since its creation, Haring’s mural has long become the pride of Woodhull. “It is part of the hospital,” said Dr. Lisa Scott-McKenzie, Woodhull’s chief operating officer, who back in ‘86 had just started working as a secretary there and did not at that point know who the mysterious painter on the scaffolding was. The mural is “deeply ingrained in who we are, and the respect that we have for our community.” According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Haring in his lifetime created more than fifty murals for hospitals, daycare centers, charity venues, and orphanages during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, and the Woodhull mural is estimated to be worth millions of dollars today. In 2018, a $20,000 restoration project was carried out by art conservators Helen Im and Suyeon Kim, who touched up some of the more damaged areas, helping to keep the mural as vibrant as it ever was.

Figure Balancing On Dog/2 Dancing Figures, 17 State Street

Across the street from the Battery in Lower Manhattan, there are, in fact, two steel sculptures made by Haring on view at 17 State Street Plaza, both part of the Lever House Art Collection. The first piece is “Untitled (Two Dancing Figures)” and consists of two characteristically Haring-esque humanoid figures with interlocked arms, kicking their legs up as if frozen in dance. One figure is colored ketchup red, while the other is mustard yellow. This particular piece was made in 1989 by Haring and is one of several versions of this exact sculpture that the artist made. Quite often, and certainly in this case, Haring created figures with the intention of capturing the essence of movement and dance. Haring often aimed to infused his art with a contagious spirit of joy and celebration, and this sculpture is no exception.

The second piece at 17 State Street is a monochromatic sculpture called “Untitled (Figure Balancing on a Dog)” which was created by Haring in 1986 and features his iconic image of a barking dog entangled with yet another humanoid figure. This sculpture is also typical of Haring’s playful, graphic style, and a nearly identical version stands in Haring’s hometown of Kutztown, Pennsylvania. This particular sculpture at State Street stands 12-feet by 10-feet by 10-feet. Keith Haring once wrote in one of his journals: “The public has a right to art. The public is being ignored by most contemporary artists. Art is for everybody.” Given that both of these sculptures are situated outside, fully accessible to the public, Haring would certainly be proud of their placement were he alive today.

Plaza 33, 250 West 34th Street

In 2015, a pedestrian-only plaza, called Plaza 33, opened up, closing off 33rd Street between Seventh Avenue and Madison Square Garden in Manhattan. The space featured planters, benches and bleacher seating areas, but also contained two sculptures available for public viewing. The first was “Brushstroke Group” by Roy Lichtenstein, which was placed near the plaza entrance on Seventh Avenue. The second, however, was “S-Man” by Keith Haring, a blue-hued steel sculpture centered on the mid-block pedestrian corridor. The Haring sculpture’s placement also marked the entrance to the pop-up food market Urbanspace Penn Plates. “S-Man” features another recurring Haring humanoid character, whose arms weave around and through its own body, forming the shape of the letter “S.”

Crack is Wack, East 127th Street

Perhaps Keith Haring’s most well known public art piece in New York City, the Crack is Wack wall is a large-scale mural first created in 1986 by the artist at what is now called the Crack is Wack Playground, located along Harlem River Drive between East 127th and 128th Streets. Initially painted on the northern face of a handball court wall, Crack Is Wack was initially painted by Haring on June 27, 1986 without having been commissioned or even been given legal permission at all. The artist, of his own volition, set out to create the guerrilla work as a warning against crack cocaine use, which was rampant across the United States during the mid to late 1980s.

Upon completion of the mural, which was composed of Haring’s signature kinetic figures and abstract forms in bold outlines, Haring was arrested by the New York City Police Department for vandalism of city property and faced potential jail time, in addition to heavy fines. Media sources like The Washington Post and The New York Post, alongside city locals, however, verbalized their support of Haring's mural in the wake of the crack epidemic and Haring ended up pleading guilty to a reduced charge of disorderly conduct, paying only a $100 fine.

Shortly thereafter, however, the mural was vandalized and transformed into a pro-crack mural that read ''Crack Is It." It was then painted over in gray by the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. The Parks Department commissioner Henry J. Stern then officially invited Haring to paint a new mural, and Haring returned to the original site on October 3, 1986, creating a new arrangement of different figures, this time painted on both sides of the handball court.

Four years later, Keith Haring died of complications from AIDS on February 16, 1990. In 2007, the Keith Haring Estate financed the first restoration of “Crack Is Wack.” A group of artists titled Gotham Scenic, who specialize in set design and mural restoration, carried out the extensive repainting of the mural. Natural deterioration elicited further repainting efforts in 2012 and the Keith Haring Foundation sponsored the most recent and most extensive restoration which was completed in 2019 by artists Louise Hunnicutt and William Tibbals. In order to slow future exfoliation of the mural, a more durable paint system was employed.

BONUS: Altarpiece: The Life of Christ, Cathedral of St. John the Divine

This last one is a bonus because it’s *technically* not free—admission to the historic Cathedral of St. John the Divine is $15 for adults, $12 for seniors and $10 for students for sightseeing purposes, however if you visit for the sake of prayer or meditation, you will be welcomed in without charge. So even if you’re not a particularly religious or spiritual individual, perhaps a visit to see one of Keith Haring’s last and most emotionally resonant works could put you in the mood to worship, even if it’s directed towards Haring himself.

Keith Haring's altarpiece, called "Life of Christ," sits within the Cathedral and was completed just a few weeks prior to his death on February 16, 1990. Haring created this 600-pound bronze triptych finished in white gold leaf, which tells the story of Christ, albeit in his signature, exuberant figures. According to a firsthand account by his friend Sam Havadtoy, Haring used a loop knife to draw the altarpiece into clay: “the images came directly from his head…He never stopped to rethink the line; he never edited himself and never made corrections. The lines he carved in the clay were seamless, flawless.”

The piece is filled with Haring’s versions of religious iconography—there’s a baby held by a pair of hands; hands ascending toward heaven; Christ on the cross. On one side panel he depicted the resurrection and on the other, a fallen angel. While several other editions of this piece are housed in nine different locations around the world, including in several other churches and museums, none hold as much weight as the one displayed on the altar of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, which is exactly where Haring’s memorial service was held, shortly after his untimely passing. Haring’s estate donated this particular work to the Cathedral in his honor, and the experience of seeing it there can be quite a moving one.

Made at period in his life when Haring was likely both grappling with and coming to accept his fate, Haring created this final work in order to impart a lasting legacy of hope, peace, and eternity. Havdtoy also described the exact moment when Haring had finished creating this piece. The typically lighthearted artist stepped back, and gazing at what would knowingly be one of his final creations, said “Man, this is really heavy.”

Did I miss any of Keith Haring’s publicly available works in New York City? Let me know!

https://gaycenter.org/culture/haring-bathroom/

Thank you for this beautiful roundup of Keith’s work. I’ve made several pilgrimages to St. John the Divine to be with the altarpiece, and it always moves me to tears. There’s such a special energy that radiates from the work, one that’s certainly “heavy” as much as it is hopeful. 💙

I’m so glad I came across your newsletter in the QStack directory. I’ve followed your Instagram account for years and am so happy there’s another outlet to engage with your work!