Where Warhol Worked (*Partied) - Part 1

"The Factory" was Andy Warhol's studio and party pad, which throughout his lifetime moved to four different locations.

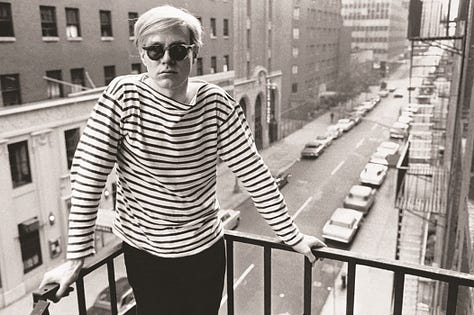

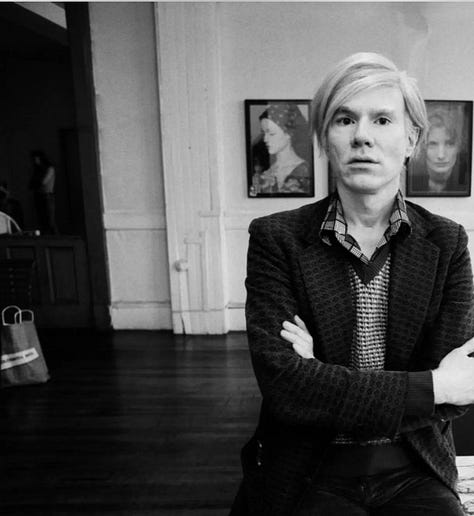

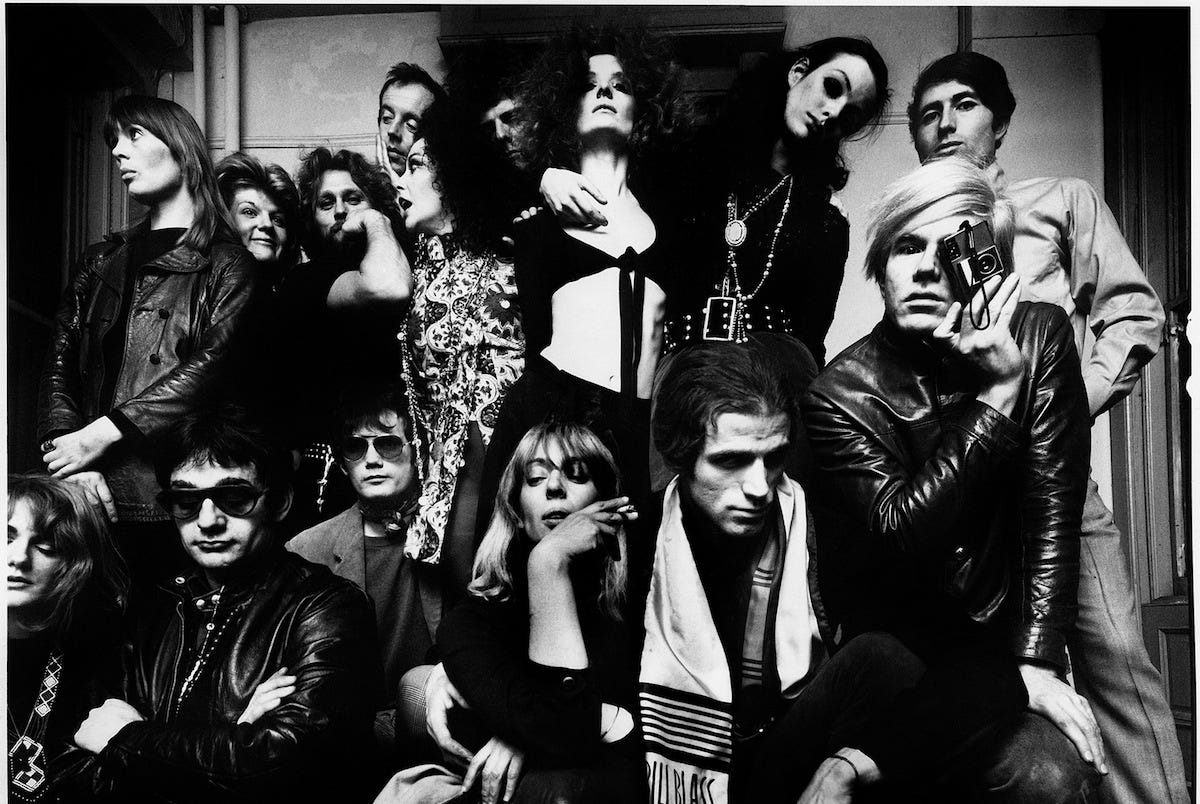

Visual artist, filmmaker, producer and leading pop art figure Andy Warhol became known for many things during his lifetime, with perhaps one of the most fabled being The Factory, the name he gave to his New York City studio that became a well-known gathering place for distinguished intellectuals, playwrights, Bohemian street people, Hollywood celebrities, wealthy patrons & countless notable LGBTQ folk. Between 1963 and 1987, The Factory in fact had four different locations, the first of which was located on the fifth floor of 231 East 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan. The original Warhol Factory was often referred to as the Silver Factory, as it was quite literally decked out in silver, covered floor to ceiling in aluminum foil and spray paint. Each Factory location, however, would become known for their own distinctive features and be associated with different eras of Warhol’s illustrious career.

By the early 1960s, Andy Warhol found himself for the first time in need of a large studio where he could paint, silk screen and make art, as his work was now causing too large of a mess at his home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side at 1342 Lexington Avenue between East 89th and 90th Streets. A friend of Warhol’s soon found an old unoccupied firehouse located at 159 East 87th Street and Warhol began working there in January 1963. Due to its decrepit nature, no one was eager to utilize the building and so the rent that Warhol paid for the whole thing was $150 a month. “The firehouse only cost $150 a month, but it was a wreck, with leaks in the roof and holes in the floors, but it was better than trying to make serious paintings in the wood-paneled living-room of his Victorian townhouse, as he’d done for the previous couple of years,” said Blake Gopnik, author of Warhol (or Warhol: A Life as Art). Warhol created his famous Death and Disaster painting series here, but just a few months later, was informed that the building would soon have to be vacated, and his lease was terminated in May. In 2016, that building, billed as “Andy Warhol’s First New York Studio”, sold for a whopping $9.98 Million. Inflation, am I right?

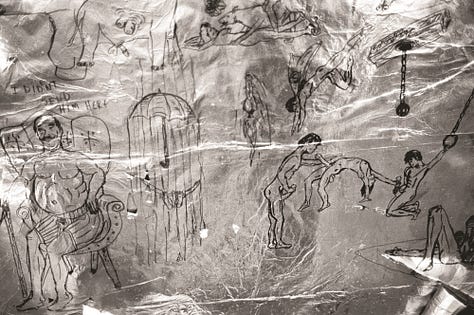

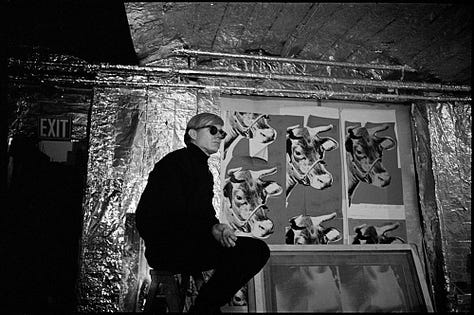

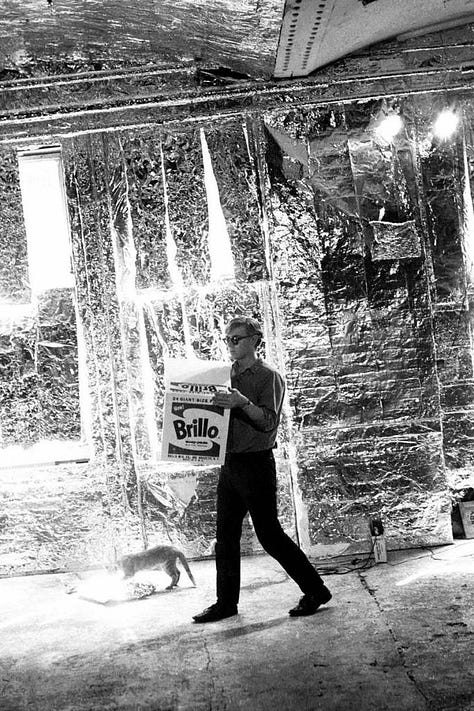

In November of that year, Warhol found himself another loft to turn into a studio, this time on the 5th floor of 231 East 47th Street, between 2nd and 3rd Avenues. While Warhol’s first studio is largely forgotten, it is this second location that would become known as the first official Warhol Factory. In 1963, artist Ray Johnson took Warhol to a "haircutting party" at photographer Billy Name's apartment, which had been decorated with tin foil and silver paint. Infatuated with the look of it, Warhol asked Name if he could do the same scheme for his recently leased loft, noting that silver, fractured mirrors and tin foil were some of the basic decorating materials loved by early amphetamine users of the 1960s. Name obliged, and proceeded to cover the whole Factory from floor to ceiling in silver, including the elevator and bathroom. Warhol's First Factory immediately became visually iconic, and his years there are thus often referred to as his Silver Era. Aside from prints and paintings, Warhol produced shoes, films, sculptures and commissioned work in various other genres to brand and sell items with his name while working here.

Billy Name also brought in a plush red couch to The Factory after finding it on the sidewalk of 47th street during one of his "midnight outings”, which became a prominent furnishing at the space. The sofa was often situated next to another incredible piece of furniture, what can best be described as a disco ball coffee table shaped like a flying saucer (apparently, East Bay Express artist Terry Furry recreated the table in 2009, using 2,000 tiny glittering mirrors). How can I get one?? The red sofa in particular quickly became a favorite place for Factory guests to crash overnight, usually after a speed come-down. It also was immortalized by being featured in many works from Warhol’s Silver Era, including in his films Blow Job (1963) and Couch (1964) (the name says it all!). Sadly, that couch would be stolen in 1968 during a move after being left unattended on the sidewalk for a short time.

But back to the mention of those speed come-downs for a moment. That’s because Warhol’s first Factory became legendary in part due to the numerous parties and gatherings he threw there, as well as for the revolving door of kooky, famous, and iconoclastic characters who frequented the place, many of whom would come to be called the Warhol Superstars, and many of whom were LGBTQ. These included the likes of Holly Woodlawn, Penny Arcade, Joey Arias, William S. Burroughs, Jackie Curtis, Joe Dallesandro, Candy Darling, Halston, Victor Hugo, Keith Haring, Jed Johnson, Ondine, Taylor Mead and countless others. In a letter dated November 15th, 1965 the President of Elk Realty, Warhol’s landlord for the Factory, helped shine a light on the nature of the artist’s parties, writing to him thus:

“Dear Mr. Warhol, We have been advised that you have been giving parties in the…space occupied by you. We understand that they are generally large parties and are held after usual office hours. We have found that your guests have left debris and litter in the public areas which you have never bothered to clean. Further, we feel that a congregation of the number of people such as you have had may be contrary to various applicable governmental rules and regulations and also might present a serious problem with the Fire Department regulations. Your lease, of course, does not permit such use and occupancy and you hereby [are] directed not to have any such parties in this building.”

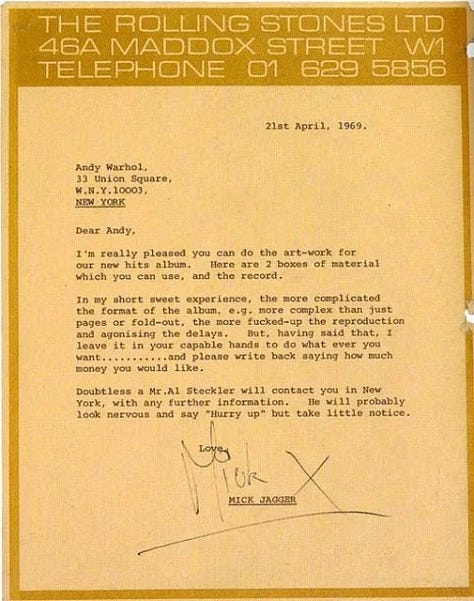

In 1967, Warhol left behind his first Factory when he was informed that the building had been sold and was scheduled to be torn down to make way for a new apartment building. Perhaps, his landlord had just gotten too fed up with perpetual cleanup duties. But the building was in fact torn down and is now currently home to One Dag Hammarskjöld Plaza, a 628-foot tall skyscraper designed by Emery Roth. Warhol then relocated his studio to the sixth floor of the Decker Building at 33 Union Square West near the corner of East 16th Street. The second iteration of The Factory was notably close to Max’s Kansas City, a nightclub and restaurant located at 213 Park Avenue South, that Warhol and his entourage frequently visited and which was known as a famous gathering spot for musicians, poets, and artists including the likes of queers such as Robert Rauschenberg, Allen Ginsberg, Fran Lebowitz and Philip Johnson.

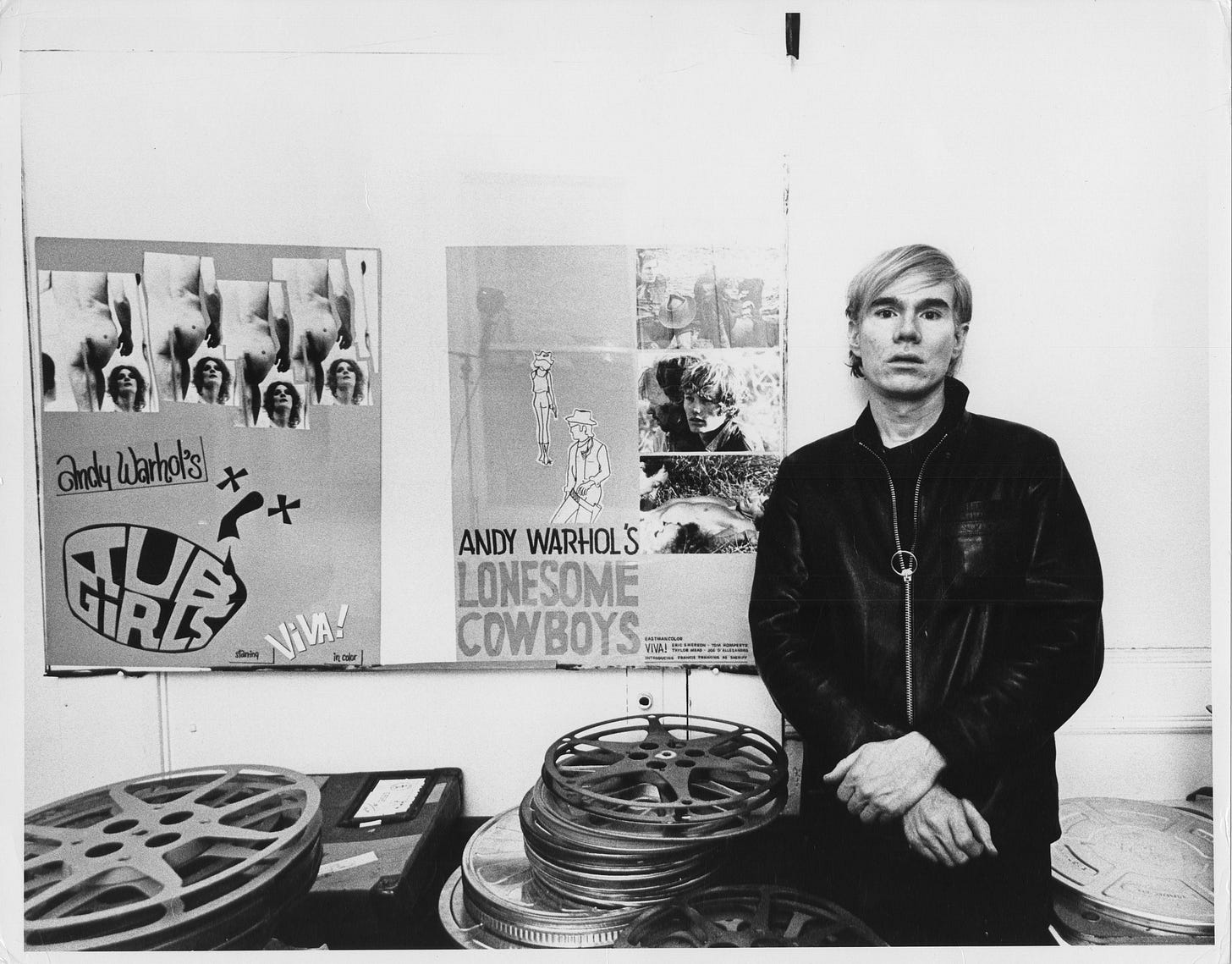

By the time he had located to the second Factory, Warhol had achieved a level of fame that left him working day and night on his paintings. At this juncture, he began to lean more into using silkscreens, which allowed him to mass-produce images more efficiently in the same manner in which corporations mass-produced consumer goods. In addition, Warhol also leaned more into the “Factory” notion by building up his roster of Superstars, attracting a ragtag bunch of adult film performers, drag queens, musicians, drug addicts and more to become his “art-workers”, helping to increase production even further. These assistants aided in the creation of paintings, starred in films, scouted new talent (Victor Hugo, for example, famously scouted new male actors for Warhol after sleeping with them) and contributed to the overall factory-like atmosphere for which Warhol’s Factory became known.

Warhol’s second Factory location, however, is most perhaps most notorious as being the venue at which the artist was shot in 1968 by Valerie Solanas. Solanas, an American radical feminist lesbian known for self publishing the iconic work, SCUM Manifesto, first encountered Warhol and the Factory in 1967 when she asked him to produce a play she had written entitled, Up Your Ass. Warhol allegedly accepted the manuscript for review, told Solanas that it was "well typed", and promised to read it. According to legend, however, Warhol, whose films had often been shut down by the police for obscenity, found Solanas’ script so pornographic that he neurotically thought it was part of a police entrapment. When Solanas followed up with Warhol about the script, he told her that he had unfortunately lost it, and instead jokingly offered her a job at the Factory as a typist. An insulted Solanas then demanded money for the lost script but instead, Warhol paid her $25 to appear in his film I, a Man (1967). At the time and despite it all, Solanas was reportedly satisfied with her experience working with Warhol and with her performance in the film, and subsequently received a nonspeaking role in one of his next films, Bike Boy (1967).

After self-publishing her SCUM Manifesto later that year, Solanas signed an informal deal with publisher Maurice Girodias, whom she felt immediately screwed her over. Solanas soon believed that a conspiracy was behind Warhol's failure to return her Up Your Ass script and that Warhol was coordinating with Girodias to steal her work. On June 3, 1968, Solanas went on a frantic spree, looking for Girodias and others whom she felt were involved with the plot against her. She eventually found herself waiting outside the Factory, where she encountered Morrissey, who asked her what she was doing there. Solanas replied, "I'm waiting for Andy to get money." Morrissey tried to get rid of Solanas, telling her that Warhol was not coming in that day, but she informed him that she didn’t mind waiting. At 2:00 PM, Solanas went up into the studio and rode the elevator up and down until Warhol finally boarded it. After a brief encounter with Warhol and Morrissey, Morrissey then went to the bathroom, while Warhol went to answer a phone call.

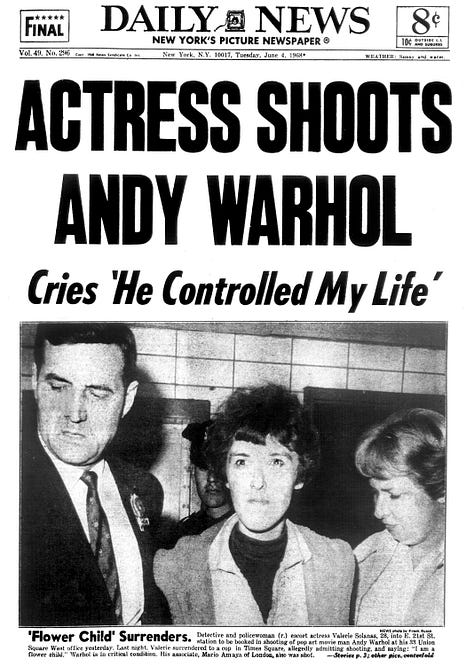

While Warhol was on the phone, Solanas fired at him three times. Her first two shots missed, but the third went through his spleen, stomach, liver, esophagus, and lungs. Solanas then shot art critic Mario Amaya in the hip and tried to shoot Fred Hughes, Warhol's manager, when her gun jammed. Hughes then asked her to leave, which she did, leaving behind a paper bag with her address book on a table. Later that day, Solanas turned herself in to the police, gave up her gun, and confessed to the shooting, stating that Warhol "had too much control in my life." She was fingerprinted and charged with felonious assault and possession of a deadly weapon. The next morning, the NY Daily News ran a front-page headline: "Actress Shoots Andy Warhol." Solanas demanded a retraction of the statement that she was an actress, explaining, "I'm a writer, not an actress."

At her arraignment in Manhattan Criminal Court, Solanas denied shooting Warhol because he wouldn't produce her play but said that she did it "for the opposite reason", because "he has a legal claim on my works." She told the judge that "it's not often that I shoot somebody. I didn't do it for nothing. Warhol had tied me up, lock, stock, and barrel. He was going to do something to me which would have ruined me." Solanas additionally opted to represent herself in court and insisted that she had no regrets. The judge struck Solanas' comments from the court record and had her admitted to Bellevue Hospital for psychiatric observation as a result. Warhol, meanwhile, was taken to Columbus–Mother Cabrini Hospital, where he underwent a successful five-hour operation, but was never quite the same again. He would famously go on to show his body’s horrendous scarring from the shooting in photographs and artworks for the rest of his life.

Stay tuned for part two and details on Factories three and four, next week!